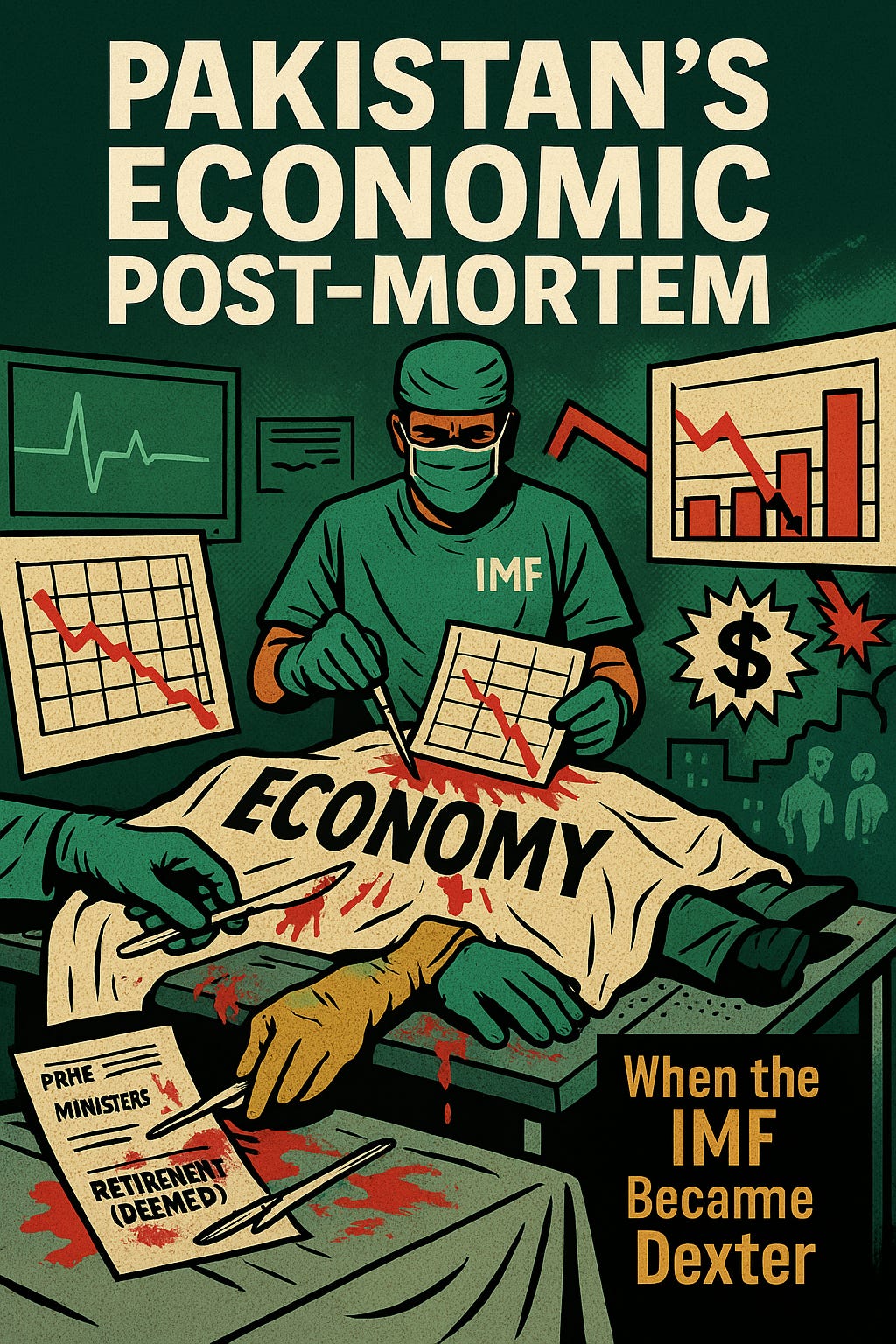

Pakistan’s Economic Post-Mortem: When the IMF Became Dexter

Inside the IMF’s unprecedented governance autopsy—corruption mapped, institutions dissected, and a system laid bare

We all know Dexter Morgan, the forensic blood-spatter genius who understands blood better than anyone (because he spills it often in his side hustle as a serial killer on Showtime’s 9 season-long thriller series named after him). The IMF, Pakistan’s lender of last resort, plays a similar double role: it diagnoses our economic wounds with surgical precision, then delivers the fatal cut when our government is pretending to play happy and healthy. Like Dexter, the Fund knows exactly how a body dies because it’s been watching the bleeding for years—and now it’s telling Pakistan, in gruesome detail, what has killed it.

With its latest Pakistan: Governance and Corruption Diagnostic Report, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has not issued a routine review. It has delivered a damning autopsy, published on November 20 after a three-month delay, the report is an overdue examination of how Pakistan’s state actually functions—not how it claims to. The report may be standard IMF fare, but Finance Minister Mohammad Aurangzeb’s choice to publish it has raised eyebrows. Some wonder whether this openness is his way of signaling independence — a gentle step away from Ishaq Dar’s entrenched influence over Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance.

Still, the report is out, and its bluntest line is also its thesis: “Corruption is a persistent and corrosive feature of Pakistan’s governance.” Here’s the good news: the IMF claims that if Pakistan implements fifteen key reforms—ranging from transparent procurement and mandatory asset declarations to restoring independence within State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)—the country’s economy could grow 5 to 6.5 percent faster over the next five years. But that projection comes with a major qualifier: elite capture, opaque institutional corridors, and discretionary rule-making have to stop; they are the reason Pakistan’s growth forecast for fiscal year 2026 has been cut to 2.7 percent.

This is not a mere fiscal commentary. It is a political autopsy—one the government tried to keep buried until the IMF forced it onto an official website.

What This Report Actually Is

The IMF’s diagnostic dissects the full span of Pakistan’s governance machinery: taxation (which is shaped by complexity, loopholes, and policy capture), budgeting (which suffers from opacity and politically driven allocations), procurement systems (which remain discretionary, non-competitive, and vulnerable to manipulation), public investment, State-Owned Enterprises or SOEs (which are deeply politicized, inefficient, and shielded from accountability), regulatory bodies (which lack independence and are routinely captured by the interests they are meant to regulate), the judiciary (which is slow, inconsistent, and unable to reliably enforce contracts or protect rights), the National Accountability Bureau or NAB (which deploys selective enforcement and reports unreliable “recovery” figures), the Federal Investigation Agency or FIA (which faces political interference, weak capacity, and credibility issues), and anti–money laundering structures (which remain fragmented, under-enforced, and prone to political influence).

This needs to be appraised and absorbed honestly and diligently by both GHQ and the Prime Minister’s Office. It is not opinion, not speculation, and not a politicized opposition narrative. It is an official mapping by the world’s lender of last resort about those who hold power, how their decisions are made, and where corruption has become the architecture of the current dispensation.

The headline number—NAB’s claim of over Rs 5.31 trillion in “recoveries” over two years—is treated with open skepticism. The IMF makes clear the figure is not reliable, not a measure of corruption, and not proof of performance. It is a symbol of the larger problem: a system that can no longer tell the truth about itself. Yes, it also means that the country’s anti-corruption watchdog is fudging the numbers.

A System Designed for Capture

The IMF’s diagnosis is stark.

Pakistan’s political economy incentivizes capture, not competition.

Large swathes of the economy remain dominated by the state.

State-Owned Enterprises and their custodians operate with vast discretion.

Regulatory bodies lack independence, capacity, and credibility.

The rules are so contradictory and so complex that discretion becomes a kind of soft currency—one that buys harassment, exemptions, delays, or enforcement depending on who is asking and who is paying.

The judicial system, described as “organizationally complex” and unable to reliably enforce contracts or protect property rights, completes the cycle. Without predictable justice, corruption is not a risk—it is a guarantee. It flourishes because nothing deters it, and nothing punishes it consistently.

How It Plays Out in Pindi & Isloo (we like to call it Pindoo)

Pakistan’s Twin Capitals – Islamabad and Rawalpindi – must take note. The press – even the local, muzzled version, is having a field day with the report. Here is where the narrative is headed:

Eyes on the ruling PMLN for selective targeting: The IMF diplomatically avoids naming individuals, but Pakistan’s politics provide the case studies. High-profile cases like Hamza Shahbaz’s money-laundering and sugar-scam investigations quietly dissolved once political winds shifted. This is precisely the kind of selective enforcement the report implies: accountability applied as a tool, not a principle.

Eyes on the Army: The IMF’s scrutiny of the military-run Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) is even sharper. It describes SIFC’s transparency and accountability frameworks as “untested,” a restrained way of saying that enormous economic influence sits behind a curtain. Opaque military-linked investments, preferential treatment for certain SOEs, and layers of parallel governance structures exacerbate the core problem: too much power in too few unaccountable hands.

Eyes on the Babus: The Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) is portrayed as a system riddled with vulnerabilities—harassment, facilitation payments, and policymaking shaped by “undue influence.” The issuance of 168 Statutory Regulatory Orders (SROs) in a single year underscores the IMF’s point: the system delivers flexibility for the elite and rigidity for the ordinary.

As former minister Taimur Khan Jhagra noted while citing the IMF’s language, Pakistan’s tax policy is “reactionary” and “open to undue influence.” That is the polite version. The lived version is that loopholes are manufactured while enforcement is selectively weaponised.

What Economists, Politicians, and Journalists Are Saying

The report has ignited a national argument—not just about corruption, but about truth, power, and narrative. The debate is fierce, but the common thread is unmistakable: whether in alarm or defensiveness, the country’s leading voices accept that the IMF has exposed something fundamental.

Economists, broadly speaking, treat the diagnostic as a long-overdue reckoning. Former banker and economics lecturer Ayesha Liaqat called it a moment of clarity, arguing on November 20 that Pakistan’s institutions are “eating the country’s potential” and that governance reform is no longer optional but existential. Strategic analyst Zohaib Ahmed offered a more skeptical angle on the same day, warning that the IMF’s headline numbers are designed to enforce compliance rather than expose a singular Pakistani pathology.

Politicians handled the report as expected—by weaponizing it. Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) leaders immediately framed it as a charge-sheet against the Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz (PML-N) government. Former minister Asad Umar warned that the report links corruption directly to declining GDP growth and demanded transparency in the Special Investment Facilitation Council. PTI’s economic spokesperson Muzzammil Aslam pointed to the IMF’s downgrade to 2.7 percent growth for the next fiscal year, calling it another failure of the Shehbaz Sharif administration. Even broader economic distress—falling exports, collapsing manufacturing, worsening inflation—was tied back to the IMF’s governance critique, with PTI leaders suggesting that the government lacks both ideas and legitimacy. As former minister Taimur Khan Jhagra noted while citing the IMF’s language, Pakistan’s tax policy is “reactionary” and “open to undue influence.” That is the polite version. The lived version is that loopholes are manufactured while enforcement is selectively weaponized. Meanwhile, pro-government voices remained muted, offering little more than defensive interpretations of revenue reform and fiscal constraints.

Journalists reacted with a mix of alarm, scrutiny, and frustration. Reporters such as Rizwan Ghilzai of Express News and independent journalist Rizwan Shah amplified the report’s language about elite capture and governance failure, urging viewers to connect the dots between corruption and economic decay. Senior journalist Asma Shirazi highlighted the government’s three-month delay in releasing the report, framing it as yet another example of elite capture—an elite hiding a document that explicitly accuses elites of capture. Economic correspondent Shahbaz Rana connected the IMF’s findings to long-ignored warnings about poor taxation policies and collapsing industrial competitiveness. Interestingly, Khurrum Husain of the Dawn – one of the foremost voices in Pakistan’s journalism, hadn’t weighed in about the report on his X account or elsewhere at the time of this publication.

The Invisible State Behind the Structure

The IMF does not name specific power centers. It does not need to. By mapping a governance system where discretionary bodies like the Special Investment Facilitation Council operate without transparency, where State-Owned Enterprises act as patronage networks, where regulations can be rewritten overnight, and where courts cannot deliver reliable remedies, the report implicitly points to the true custodians of the state.

Every Pakistani understands the silhouette behind those institutions. The IMF has merely sketched its outline.

What the IMF Wants Changed

Unlike previous programs, this is not about cutting budgets. It is about rebuilding the state.

The IMF calls for an independent tax policy office for the Federal Board of Revenue; an end to discretionary contracts through mandatory e-procurement; transparent judicial appointments; digitized compliance systems; clean separation between political offices and investigative bodies; and depoliticized, professional oversight of the National Accountability Bureau and Federal Investigation Agency. It also demands mandatory asset declarations and public reporting mechanisms for officials across the economic and legal spectrum.

The Final Reckoning

The deepest wound of this report is not the numbers. It is the confirmation that Pakistan’s crisis is not mismanagement but by design. The corruption the IMF describes is not the envelope slipped under a table—it is the legal framework, the Statutory Regulatory Orders, the selective prosecution, the silent closures, the elite waivers, and the parallel structures that bypass democratic scrutiny altogether.

The IMF’s verdict is simple: fix governance and Pakistan will grow. Leave governance untouched and no loan—local or foreign—will ever be enough. The question Pakistan must confront is the one it has avoided for decades: Will reform unlock this country’s potential for its citizens, or will that potential remain locked for the elite alone?

Until that question is answered, no revenue reform is genuine, no accountability drive is credible, and no IMF program can honestly claim to serve the public.

The IMF’s assessment is disturbing but unsurprising—most Pakistanis have long understood that governance failure, elite capture, and institutional decay lie at the heart of our economic crisis. What is new, however, is the clarity and bluntness with which these realities have finally been documented and the IMF's insistence that the report should be published in Pakistan. With the current political environment and entrenched power structures, meaningful reform feels almost impossible, yet this report forces the country to confront what it has ignored for decades.

I want to commend the two journalists, Shiza Mohsin and Wajahat S. Khan, for presenting this analysis with such depth, courage, and narrative sharpness. Their work has transformed a technical IMF document into a powerful, accessible examination of Pakistan’s structural problems—a public service at a moment when honest journalism is increasingly rare.

Fact!! Pakistanis people know the corrupted institutions' silhouette with pretty much good resolution. Also, feel good how the report was so blunty.

Hope it forces to redesign our institutions that can really offer progress.

Thanks for this post!